Courses Taught

General Ecology

The primary course I’ve taught at Queens College is General Ecology, for advanced undergraduates and Masters students. Lecture is a broad tour through hierarchies of ecology, from its historical foundations to the new world of conservation biology, and from individuals and populations to the biosphere. Because the course is offered in autumn, the first laboratories occur mainly as outdoors field trips to take advantage of the warmer weather. Later labs are given as classroom exercises. Field trips include visits to the ‘wilds’ of the Queens College campus itself, a heavily urbanized freshwater pond, the shores of Long Island Sound, and a forested park with pothole ponds formed by glaciers. (Photo is of an Asian shore crab, a non-native species that dominates the rocky intertidal zone in Queens.)

The Hudson River: Source to Sink

In 2005, Karin Limburg of SUNY-ESF and I guided a dozen students from both institutions from the source of the Hudson in the Adirondacks to its mouth in New York City. The theme of this eight-day trip was gradients: in elevation; river volume and velocity; water quality; biodiversity and abundances; and human population density. We traveled by van, foot, and boat and each day conducted field sampling, met experts for river side lectures, and visited key gegraphic and cultural sites. At the end of the journey Karin and I received the ultimate compliment–the by-then-well-bonded students wanted to do it again– immediately,–this time backward! (Photo is of Professor and ichthyologist Robert Schmidt of Bard College at Simon’s Rock electroshocking fish with the students where Sawkill Creek meets Tivoli Bays).

Urban Conservation Biology

This was a graduate seminar focusing on the new realm of urban conservation biology. No text for this was available; however, we read and discussed key papers, and students developed and presented term papers on topics of their choosing. We began the course by viewing my friend Rob Maass’s award-winning film on the fishing subcultures and environmental problems of New York Harbor, titled Gotham Fish Tales. (Photo is by Andy Silver of the snakehead fish he first discovered in Flushing Meadow lakes in 2005. This pair was sunning themselves among reeds and garbage in the April shallows)

Historical Ecology

Historical ecology is the new and increasingly important discipline that attempts to reconstruct earlier ecologies using whatever, and as many means as possible. Approaches may include paleontology, archaeology, written records, oral histories, modeling, and even cutting-edge molecular analyses. Much of this work fits within the new paradigm of ‘shifting baselines,’ the notion that resource managers try to hold the line on what they encounter early in their careers, and that with slippage over generations, there is an insidious and often underappreciated gap between ‘what was’ and ‘what is.’ In this graduate seminar, we considered seminal studies from the terrestrial and aquatic realms, and how their results might inform future conservation.

Marine Conservation Biology

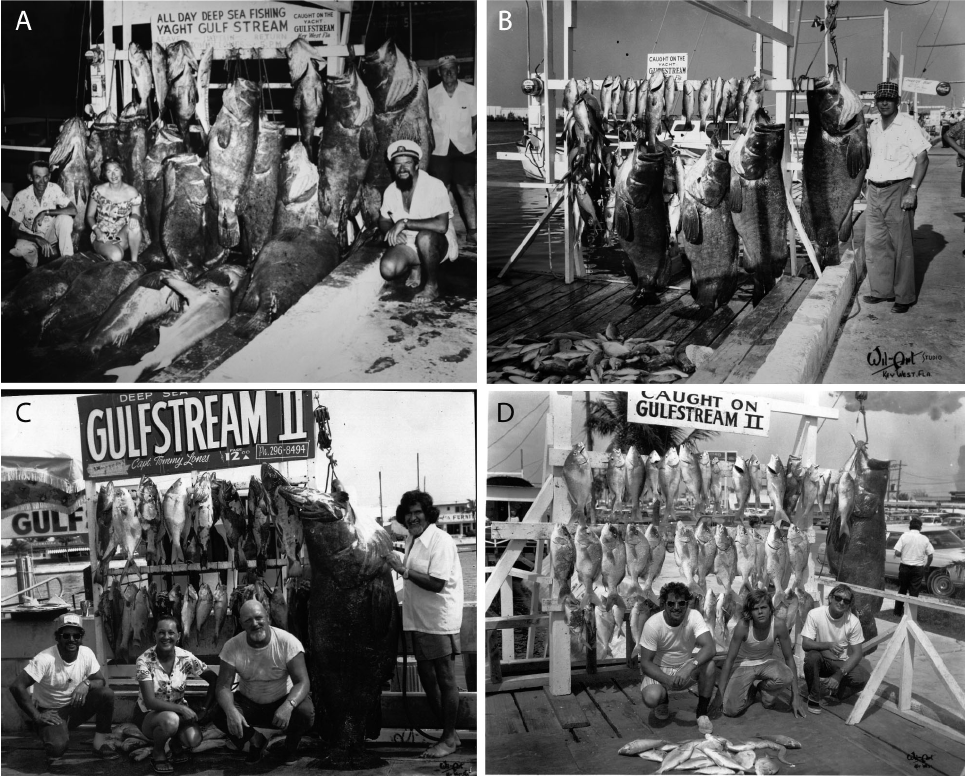

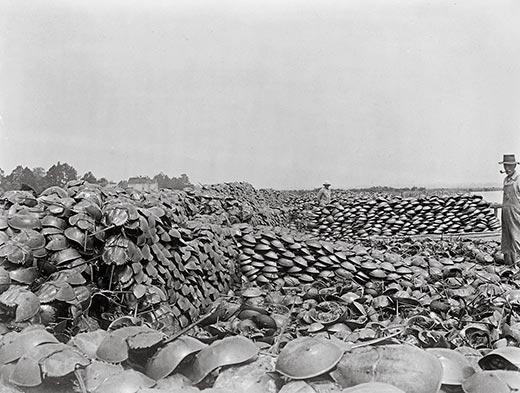

Our view of the oceans has passed from a domain so large that they were beyond harm to the sad reality that they are facing an environmental ‘Aquacalypse.’ The thematic question posed for the entire course has been “What will our oceans be like in 2050”? This is a timepoint that has been predicted by some for the seas to show critical levels of declines. Over the years the always spirited final discussions and vote among the classes have shifted towards far more pessimists than optimists, but they also pointed to the need for more marine education to help turn the tide. (The above photo is from Loren McClenachan’s already classic 2009 ‘shifting baselines’ paper on changes in sizes of fish landed at a Florida dock between 1956 and 1979. The photo below is of horseshoe crabs landed for fertilizer in Delaware Bay in 1924.)

The Nature of New York

In 2004, the well known labor negotiator and philanthropist, Theodore Kheel, made a generous donation to CUNY to found an institute to study the nature and environment of New York City. This eventually became the CUNY Institute for Sustainable Cities (CISC), housed at Hunter College. As part of this initiative, I twice led a course that examined many aspects of nature in the city, from the consequences of its geology and geography to its flora and fauna to Native American relationships with nature to present-day issues and perceptions. The course benefited from many guest lectures by regional scholars and authors. The course also inspired similar offerings at other CUNY and non-CUNY institutions. (Photo is of ‘New York City at Sunset,’ by Mark Curry, 1932).